For an edited and expanded version of this blog, see: https://mayday.leftword.com/blog/three-cyclists-from-india-and-encounters-of-empire/

Published on LeftWord Blog, 11 August 2017

From the archive (RGASPI 542/1/5, 68)

”In China, the people did not believe they were Indians, because they were clean-shaven…”

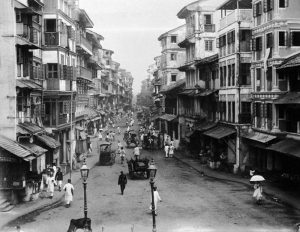

The continual mining of the Comintern Archive in Moscow, either by visiting the archive or consulting the digital archive online, furthers our understanding of (as in my case) anti-colonial and anti-imperialist movements and experiences in the interwar period. By perceiving these movements as circulations of experience, and as transnational in scope and nature, documents located in the Moscow archive tells us about previously unknown encounters and narratives that either supports already established research results or adds new layers of understanding to what really happened in Europe, the US, Latin America, Asia or Africa between the wars. Hence, what I am thinking of here is the combination of global and transnational perspectives as a theoretical and methodological way of understanding history and historical processes. One example of this is the story of three cyclists’ from India who departed from Bombay (nowadays: Mumbai) sometime in 1923 for ”a world tour”, only to return four years later to the same city. In the files of the League against Imperialism, according to one of the organization’s official publications, ”Press Service” (1927), the following remarkable transnational tale of imperial encounters in China, Indo-China and the US unfolds itself.

The three Indian cyclists’ left Bombay in 1923 with the intention of visiting and experiencing new vistas and meeting other cultures rather than reading about it. Returning back to India in 1927, it had been a journey covered first, on wheels, and second, it had deepened their insight into the ”methods of Japanese, French, American and British imperialism.” According to the ”Press Service”, what they had seen ”convinced them of the urgent need of national independence,” which, in hindsight was an echo of the initial points declared by the US President Woodrow Wilson at the Versailles Peace Conference in 1919, an epochal event that faded rather as power interests took the leading role, but which found new impetus with the official establishment of the League against Imperialism in Brussels 10-14 February 1927. Hence, it was all about continuing the need of declaring and furthering the demands of the colonies to receive national independence based on the premises of national self-determination. What did the three cyclists, of whom there is little known after just reading the report in ”Press Service”, experience on the journey through Asia, reaching all the way to the US and back again to Bombay?

If we adopt a geographical perspective, the cyclists’ encountered various forms of racial prejudice and segregation, either openly or moderately expressed. Arriving in Korea they were welcomed and ”received a very heartily” reception wherever they went with their bicycles. As ”victims of Japanese imperialism”, the Koreans connected with the Indians and their heritage of belonging to a ”great land” that had been subjected to cruel exploitation by the British ”for over a century and a half”. In Indo-China, the three cyclists’ got to know very well the ”blessings of French imperialism”, a statement that explicitly referred to the most stringent and racial laws against Indians and the Chinese that had been put into effect to subject them for the reason that they were ”regarded as pariahs by the French authorities”. Different treatment of nationalities also emerged during the journey, and as was noted, the Japanese population in Indo-China was exempted from discriminating laws and given the status of ”civilized beings” in comparison with the Indians and Chinese. As the adventure finally reached the US, and as the three cyclists’ made port in San Francisco, they could read on signboards in many places that ”Japs, Chinese, Indians, Dogs and Cats not allowed.”

Thus, as much as racial prejudice was a natural feature in various national contexts, it was also increasingly transnational in scope and intent wherever the three cyclists’ chose to steer their direction. The report in ”Press Service” concludes the impressions of imperialism made by the cyclists’ after ”the world tour”. Accordingly, French imperialism was as far away as possible from the national insignia of ”liberty, equality and justice” as it was put into practice in the French colonies, whereas British imperialism came as no surprise to the three Indians, meaning, it was pretty evident that all means were taken by British colonial authorities to act as ”protector of the interests of British nationals.”

This single document outlines in general terms the fundamental approach of ”thinking transnational”, or as Akira Iriye writes in Global and Transnational History (2013): ”[T]ransnational history, … focuses on cross-national connections, whether through individuals, non-national identities, and non-state actors, or in terms of objectives shared by people and communities regardless of their nationality.” Hence, what the encounter of these three unidentified cyclists’ from India tells us is that regardless of identifying themselves as ”Indian”, communication and travel across continents during four years was made possible with mechanical means: the bicycle, and through this vehicle, this enabled encounters and meetings of a novel kind that changed their understanding of colonialism and imperialism.